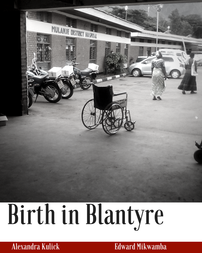

About Birth in Blantyre:

Birth in Blantyre was released March 1st through Esther's House Publishing with the sole purpose of raising awareness and funds to supply needed supplies to hospitals in Malawi. The project required forging relationships with people on the ground in Malawi (doctors, nurses, moms, and pastors) as well as in the United States. It also took in-depth investigation to understand the five-fold issue of the developing healthcare system.

Excerpt:

Excerpt: page 3-10

Malawi is a landlocked country in southeastern Africa, surrounded by Mozambique, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Zambia. A country that is roughly the size of Pennsylvania is home to over 18 million people. Like many other developing countries, Malawi faces an array of challenges including 980,000 adults living with HIV and a staggeringly high unemployment rate.

The Malawi Demographic and Health Survey revealed that 439 per 100,000 women die during pregnancy and birth, ranking Malawi amongst the countries with the highest maternal mortality rates in the world (Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015-16). To most women in the western world, the thought of dying in childbirth and not being able to raise your newborn is horrifying. Picking out nursery paint colors and registering for gifts far overshadows preparing a last will and testament, yet on a worldwide basis, 830 women will die from preventable causes during pregnancy and childbirth each day (WHO, 2016).

After writing my first book on pregnancy, I began to hear heartbreaking stories from women struggling in Malawi. I wanted to do more to help them but first, I had to understand the problem. I envisioned babies being delivered by untrained assistants with outdated procedures, so I arranged an interview with Catherine Chande, a retired midwife and nurse at Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Armed with preconceived notions and basic questions to understand routine prenatal care, I braced myself to be shocked by my first look into Malawi’s healthcare system.

The shock that I received wasn't nearly what I anticipated. Catherine shared how incredibly similar to the care women receive in the United States. Women are seen regularly for prenatal appointments, they're instructed about what is safe and unsafe during pregnancy and warning signs to look out for. Hospitals are even equipped to care for babies born before 36 weeks. So, where does the story turn from routine care to deadly?

Catherine explained that in her experience, 3 nurses would care for roughly 40 patients per shift. The sheer magnitude of such a workload can easily lead to mistakes and complications being overlooked. Typically in the United States, hospitals strive to have 1 nurse for 2 laboring women and increase the staff if complications arise to ensure proper care.

Reducing nurse workloads can drastically improve the patient’s outcome. One study found that changing a workload of 6 patients per nurse to less than 3 patients per shift would save 25 lives per 1,000 hospitalized patients (Kane et al., 2007). Increasing the number of nurses to care for the patients in Malawi could usher in drastic change, but it’s not without hindrances.

Becoming a nurse takes years of schooling and training. Though many may dream of joining the profession, the opportunity for an education seldom reaches those growing up in rural areas. Students who have the grades and money to pursue schooling are propelled by a passion which fuels them through an incredibly difficult work environment.

Hospital staff morale can be incredibly low with nurses overwhelmed by patients and working conditions. Nurse Jean, a beloved midwife, and registered nurse shared that laboring women were frequently shouted at for asking questions about their labor progress because the staff felt so much pressure.

Additionally, women seldom receive the instruction that they need to care for themselves and their babies after birth. "Three girls verbalized staying [in the hospital] for four weeks because of non-healing wounds," said Nurse Jean. "There was no proper education on the care of episiotomies."

Nurses in Malawi face low wages, long hours, and little support, making this crucial profession daunting. The shortage of staff can lead to delays in care, which can sadly turn fatal. In 2016, a comprehensive study was conducted to examine the causes of maternal deaths in a region called Mangochi, ninety-one miles away from Blantyre.

The study found that 96.8% women who died in the healthcare facilities had experienced delays in receiving care, and almost a quarter of the women died before receiving any care at all (Mgawadere, Unkels, Kazembe, & Broek 2017).

On top of the limited staff, hospitals suffer from a severe lack of resources. Shortage of supplies factored into 63% of maternal deaths in Mangochi, including a lack of antibiotics, magnesium sulfate, and blood in the blood bank (Mgawadere, 2017).

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth reports, "Three facilities had an insufficient supply of gloves and healthcare providers reserved the gloves for assessing women in the second stage of labor only. As a result, seven women experienced prolonged labor which was not detected and subsequently died of sepsis." One box of 50 latex gloves can be purchased in Malawi for $6. 7 women died in one hospital because of a 12 cent pair of gloves.