|

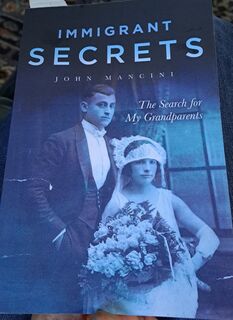

Researching relatives who ended up in an asylum often feels like staring into a brick wall. Behind it are records galore, but the mental health and hygiene laws won’t budge, so for years, I’ve stared hoping something might change. Picking up John Mancini’s book happened to be that change for me. Though John faced the same brick wall, he discovered a multitude of other avenues to follow, illuminating a portrait of both of his grandparents that he shares with his journey in Immigrant Secrets: The Search for my Grandparents. John started his journey armed with a few facts and ideas about his paternal grandparents, namely that they were Italian immigrants who died in a fire during the 1930s. Through a ship manifest, he confirms his grandmother, Elisabetta immigrated in 1920, and her future husband, Francesco followed the next year. They were married in 1924 and had their first child by the time of the 1925 census. Five years later, the census shows them with a second son living on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As I read their story, I could picture my relatives passing by their family’s fruit stand- though I’m not sure they’d have had the money to stop and buy anything. Nevertheless, reading about John’s family felt familiar in many aspects, bringing to life a world long past. Yet, the American dream unravels for Francesco and Elisabetta as dark shadows from the past tear their family apart. In lieu of a suspected fire, John uncovers that both grandparents found themselves in an asylum for the remainder of their days. John was kind enough to answer some questions about his book and his journey to uncovering his ancestors, and I hope his journey will inspire you on your own!  What inspired you to embark on your family history journey? I suppose a triggering event was the realization in the summer of 2017 that I had officially lived one day longer than the 22,834 days accorded to my father. I had officially moved into uncharted territory. The statute of limitations on being your father’s son never quite runs out, but it certainly takes on a different feel once you live longer than he did. It was in that moment that I decided to see what I could find out about my father’s parents. Another factor was becoming a grandparent and realizing that there is a strange and tenuous connection between generations. I sensed a power in being part of a bigger story, a story connected both to what was and what will be. And then the realization that we really knew nothing about my father’s backstory. Immigrant Secrets had so many wonderful details of life in Italy! Did you travel to Italy to research your family history? If so, what tips can you offer those planning research in another country? I have been to Italy three or four times, but never to my grandparents’ hometown, Itri. As I got into understanding and telling their story, I was dying to go, but surprise -- along came COVID. So, my tip is a weird pandemic one. I found that I could learn a lot by “walking around” a location using Google street view. It is quite remarkable how you can get a feel for a place without being there. I also read multiple blogs and travel books about Itri, which helped fill in the gaps. When it came to accessing records in Italy that weren’t on-line – like my grandfather’s WW1 military records – Google Translate plus some very patient people on the Italian side made a huge difference. Another resource that was terrifically helpful in understanding the life of my grandparents in the Flatiron area of Lower Manhattan in the 1930s was the Tenement Museum. For anyone with immigrant relatives who passed through New York City, a visit to the Tenement Museum – and a tour through a representative apartment – is invaluable in creating a mental picture of what life was like. In a scene in Immigrant Secrets, you mention Elisabetta going to the police because Francesco neglected to care for his family. Is this something you could find a court record for, or did you uncover that information through other documents? What was that process like? That is a good question and was quite a stroke of good luck. It’s a long story, and as I mention in the book, I had struck out with the commitment records for my grandmother. While I knew that she had been committed in 1938, I wasn’t able -- despite multiple attempts -- to review that record. I had read a terrific book by Libby Copeland – The Lost Family – and the narrative of that book centered around records at the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. I figured that if my father’s family had been one in a bit of crisis, perhaps the NYSPCC might have been involved at some point. But again COVID got in the way, and as my October 2021 publication deadline approached without additional information, I had grown used to the fact that my grandmother’s commitment would just need to be an open question. I had written that part of the book to reflect that knowledge gap. And then in early September 2021 Chelsea Frank from NYSPCC contacted me that she had found a case documenting what had happened to my grandmother in 1938 – which made for a few weeks of hectic rewrite! The commitment papers for Francesco give us a glimpse at the situation in his own words and reveal who committed him, along with the doctors who signed off on the commitment. What was it like opening that file and reading your grandfather’s words? That was a strange experience. For one thing, the Records Room at the Supreme Court on Centre Street in Manhattan is like a Records Rooms from Central Casting. My first reaction was that I was walking up to a movie set. Many films and television series were in fact shot at the New York County Courthouse, including Miracle on 34th Street, 12 Angry Men, The Godfather, Wall Street, Goodfellas, and a host of others. New York must not have gotten paid very much for these location shots, though, because the interior of the building is...well...let’s just say austere. The Court is an old building in a bit of disrepair, and to get to the Records Room you descend to the basement. So, the atmosphere was already a bit eerie. To see words from my grandmother (she was the one who committed him) and quotes directly from my grandfather from the doctors at Bellevue was an experience I won’t forget. The front of the document is still a bit jarring. “Certificate of Lunacy.” No mincing about there. And his legal status. “Indigent.” There is context to my grandparents’ story -- and the secrecy around it -- that is likely to feel alien to contemporary audiences, who love to talk endlessly about all afflictions, no matter how minor. After a brief flurry of benevolent care in the late 1800s, by the 1920s and 1930s Americans were done with the notion of individually caring for the mentally ill and helping them move back into the mainstream. By the 1920s and 1930s, Americans were intent on removing people with mental illness from their midst and were focused on simply warehousing the mentally ill -- preferably somewhere out of sight. In the book, you share how you traveled to New York to obtain the commitment hearing files in person. Are you aware if those files can be requested and sent remotely to those in other parts of the country? The state of New York is notoriously obstinate about the release of health records -- even to direct relatives and even for people long dead and even for those for whom the word “HIPAA” would have meant nothing. I won’t go through all the New York State health system dead-ends I encountered. During this journey, I came across a terrific book by Steve Luxenberg, a former Washington Post writer. Annie’s Ghosts describes his somewhat similar journey across the psychiatric commitment landscape. When his mother died, Luxenberg discovered he'd had an aunt, warehoused for many years in a Detroit mental hospital. Why? Why hadn't he and his siblings been told? He launched an investigation into his aunt's history, which led to an investigation into the asylum system itself. Each discovery raised more questions. So, I contacted Steve and asked him if he had any ideas on how to proceed. He suggested that I go down the path of finding the original commitment papers -- that legal documents have a different set of privacy restrictions associated with them than do healthcare documents. So that’s what I did. My sense is that no one was going to help copy or transfer records elsewhere. I needed to make a specific written request, and even then, there was no guarantee that the right records would show up. One suggestion for those accessing long-lost paper records: Make sure you get everything you need the first time, because there is no guarantee that old records will actually be refiled properly. Was there ever a moment when you wondered if you should leave the records in the dark and not unearth the truth? My brother and I debated whether to raise all this secret history with our mom and ultimately decided that telling the story was the way to keep my father’s story alive. We thought for a while about what to ask our mom about all of this, and what she knew. My sister says that in graduate school she needed to develop a family history as part of her child psychology degree. She told me: “I had a chart with all these empty spaces. So, I called Mom and asked her about Dad’s family. It seemed to be a distressing thing for her, so I kind of abandoned it. My first instinct was that she was protecting information. But at some point, I concluded that it was just an embarrassing thing for her to admit that she was married to this person for so many years and never knew any of this.” What changes would you like to see to the research process? I initially tried to request my grandparents’ health records from various NY state agencies, thinking this would not be difficult since I was their nearest living relative. I did so both directly and through Freedom of Information Act requests but ran into brick wall after brick wall. The refrain was always the same. Per the New York State Office of Mental Health, if you are a family member of a deceased patient, you can request information if:

Which, of course, means that for the most part, no one who cares about these records can actually access them. Along this journey, I ran into countless tragic stories of other people whose deceased relatives had been institutionalized long ago in the New York Mental Health system and had been systematically denied any information about what had happened to them. All in the name of a misguided and antiquated concept of privacy. Learn More About John and See some of the records he found here!

6 Comments

|

Alexandrais a writer & tired homeschooling mom of five. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed